A letter to the FBI agent in my webcam

Why digital surveillance is complicated, insidious, and eyeless

So I’m at dinner the other night telling my friends how I want to have a go at metalworking. I had this clever idea for a silver necklace, and I just needed to find a way to make it. As I open my phone to pass time on the subway ride home, what do I see? Instagram ads for silversmithing classes. Then I open TikTok to see a local influencer (you know the accent) talking about Three Reasons Why You Need to Try Toronto’s Newest Jewelry Making Workshop. I put my phone away and sat in silence until the mysterious subway voice announced my stop.

Digital surveillance—the ways that our online behaviour is tracked—is nothing new to most of us. For the most part, we just accept the ways that our digital footprint is traced. Siri always seems to be listening. The FBI agent in my webcam is laughing at my bedhead right now. My FYP? She gets me. We’ve reached this meta-level of awareness and even find ways to laugh about how commonplace data tracking has become.

Seeing, or being seen, is how we’ve come to understand surveillance. It’s familiar, visceral even. That prickly feeling of being watched lingers like smog in the summer air. We fixate on “the gaze” because it gives us something tangible to resist. It’s something we can block or distort. We buy tiny webcam covers to stop invisible eyes on Zoom calls (only $7.63 for a 12-pack on Amazon—what a steal!). These gestures offer a sense of control. They’re small rituals of resistance in a system that largely escapes our grasp.

But it’s not really about being seen or heard. Even metaphorically, digital surveillance is less about the gaze than it is about invisible architecture. Let’s talk about what that means.

The all-seeing eye

Before we dive into things—a super brief background on some relevant concepts.

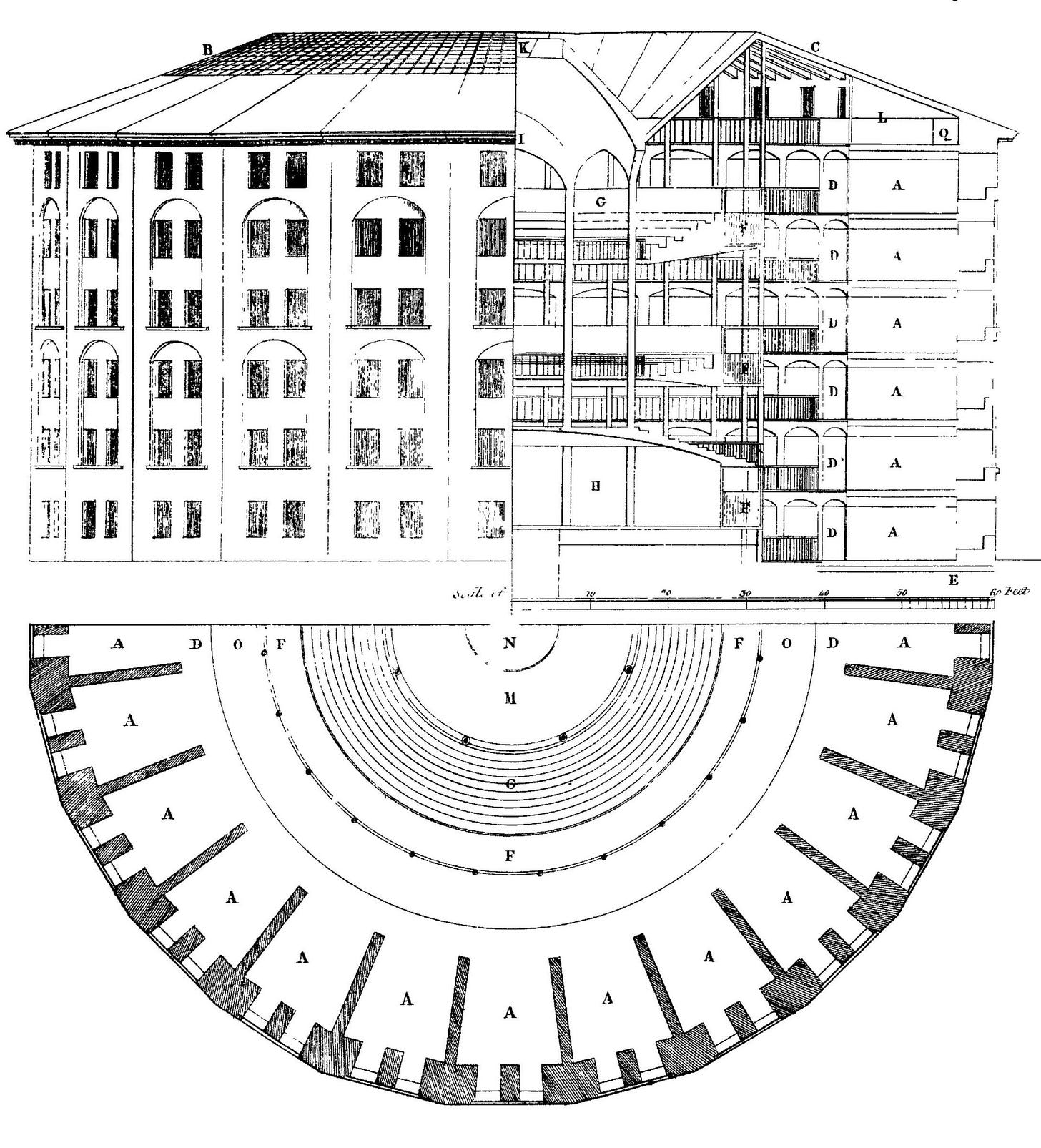

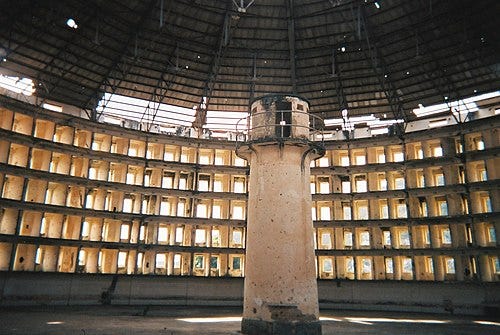

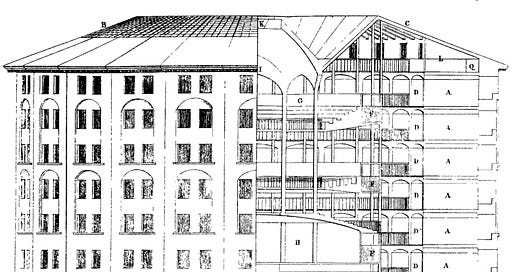

In the 18th century, English philosopher Jeremy Bentham designed a specific prison concept called the panopticon. He proposed a circular building with all the prison cells arranged around the perimeter and a guard tower in the centre. This meant that a single guard could watch all the prisoners from high above without them even knowing. Of course, there’s no way the guard could watch them all at once, but it’s the idea that the prisoners could be watched at any moment that keeps them in check.

Fast forward to the 1970s: French philosopher Michel Foucault uses the panopticon as a metaphor for how modern societies maintain power in Discipline and Punish. It used to be that a king would stand on a balcony, watching his subjects. His gaze would represent physical power: a spectacle of him seeing, and everyone else being seen. Foucault argues that in modern society, the gaze in inverted. We don’t need a king to watch us because we’ll watch ourselves—like the prisoners in the panopticon. Many scholars have interpreted this to mean that the all-seeing eye causes us to internalize the gaze, and become our own warden, so to speak.

For these reasons, the metaphor of the panopticon is everywhere in discourses about digital technology and how it maintains surveillance of our behaviours online. Soon enough, every digital trace we left behind all seemed to confirm this idea of individualized monitoring.

The thing is: no one is watching you

(Probably.)

In her essay The Inverted Eye, philosopher Petra Gehring argues that we’ve misunderstood Foucault’s panopticon. It’s not about an all-seeing eye. In fact, it’s not about the gaze at all. What Foucault really describes is the rise of automated systems—surveillance built into invisible infrastructure that no longer needs anyone to watch. It’s not that we’ve internalized the gaze; it’s that we react as if we’re visible, because the system makes visibility automatic.

Quite to the contrary, Foucault analyses virtualization and automatization procedures that – after cutting off of the King’s head – invert and eliminate the sovereignty of the gaze as well: they also rip out the sovereign’s eye. (Gehring, 2017)

Think speed cameras. You don’t need to believe in road safety and feel morally compelled to go the speed limit. It doesn’t matter why you speed, you just see the camera and instinctively slow down. Control happens not through psychology, but through infrastructure.

Bringing it to now

So what does this mean for us internet-explorers? Unlike the physical structure of the panopticon, today’s digital surveillance isn’t so easy to point to. There’s no obvious guard tower online—just a root system of platforms, algorithms, and sneaky features quietly shaping how we behave. It’s hard to self-monitor when you don’t even know what’s being tracked, or why. But still, you adjust. Not because Big Brother is watching, but just in case someone might be. Surveillance is ambient and built into the background.

Take Superhuman, the “most productive email app ever made” (sure, whatever). I learned through a friend that they sneakily track read receipts by including a tracking pixel on every email you send with their app. I haven’t been able to unlearn this. It’s not that I’m outraged because someone is actively spying on me; I’m uncomfortable with the possibility of being seen without me knowing. Suddenly, I’m rethinking when to open messages, how fast to respond, and whether to open them at all. (Read receipts are off by default now after some online outrage, but I think it’s still wrong that people can turn them on without notifying the recipients.)

All eyes on me

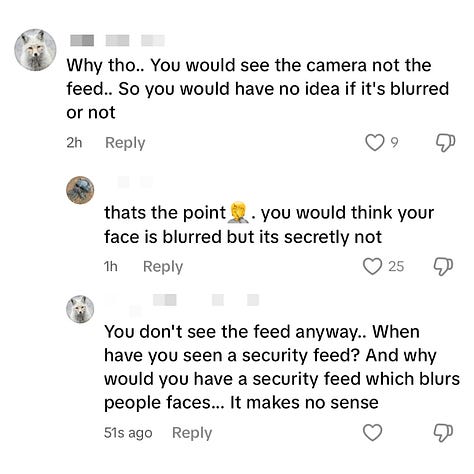

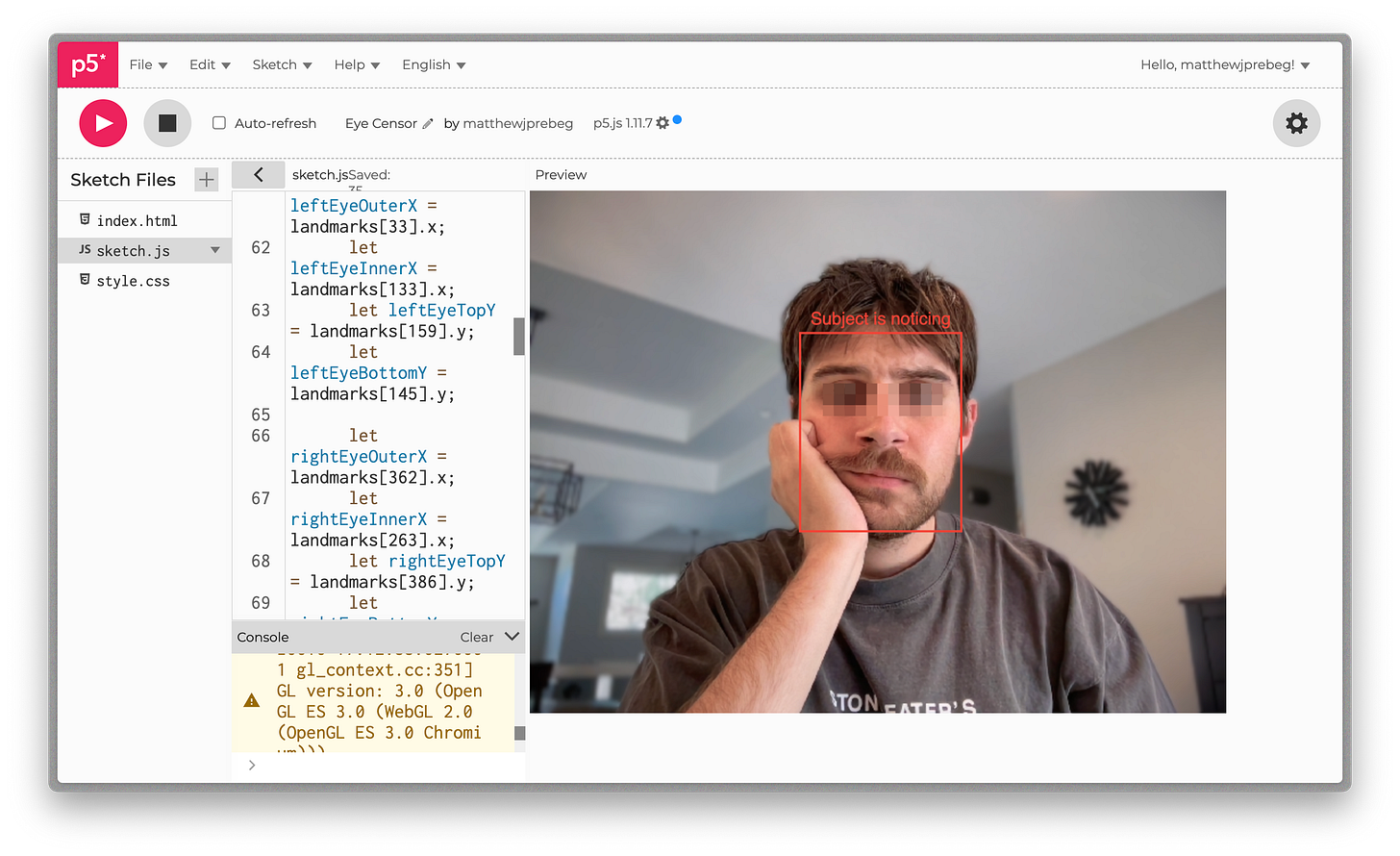

Me being me, I made a cheeky art project to play with this theme. I coded a “surveillance filter” that censors your eyes to protect your privacy, but only when you’re looking at the screen. Try it out here.

When I shared this on TikTok, it was interesting to see how people responded to it. Some people reacted with anxiety. Some were quick to demonstrate how much they know about surveillance. Others thought it was just plain useless. All of these comments sparked some really interested conversations about how surveillance sneaks into our digital lives in unexpected, unseen, and sometimes uncomfortable ways.

Cache

Apple’s Aqua Interface: With Apple’s new “liquid glass” design language coming out later this year, I came across this video of Steve Jobs announcing the aqua interface 17 years ago. We used to be a society (nb: I actually like the liquid glass though).

Lenna Image by The Pudding: This visual essay tracks the history of one of the internet’s oldest images: a picture of a Playboy model.

Metazooa: A Wordle-style guessing game about evolutionary biology where you guess the animal based on its taxonomy (I got today’s with two guesses remaining!).

Thanks for reading all the way to the end! Every few weeks, I share some research and art in the realm of the technology, culture, and people. I’m a nerd that thinks too much, and I love it and hope you do too. Until next time ++

Matt

Great read! I wrote a similar essay exploring the panopticon through the lens of public Instagram likes and what it's like growing up under constant surveillance as Gen Z. As an engineering student who's actively building these systems, I find myself struggling privacy, power and the supposed convenience these products offer. I have not found a satisfying solution, but I sure think about it a lot! https://industrialcomplex.substack.com/p/big-brother-is-always-watching-instagram